View historical precious metals price charts »

View historical precious metals price charts »

- September 01, 2023 -

By Lisa Murray-Roselli

In April of this year, $20 million worth of gold and other high-value items were stolen from Toronto’s Pearson International Airport. The gold had arrived on an Air Canada flight from Zurich, Switzerland, was offloaded, and transported to a warehouse location near the airport but outside of its security zone. It went missing soon after, likely accessed through the public side of the warehouse, which had no guards. The Brink’s company was responsible for coordinating the shipment and they are working with the police, who, as of this writing, have released no further details to the public.

Law enforcement experts have weighed in, saying that lack of communication from the police probably means that they have good information and are making progress on the case—releasing information to the public could jeopardize that progress. Their first task would be to exclude suspects through a series of interviews and background checks. Any deviation from protocol by airline or Brink’s employees would indicate that someone with inside knowledge was involved. And if history is a reliable guide, there probably was someone on the inside assisting the operation.

There is a reason that so many movies are made about colossal thefts—they take a certain brilliance to execute. And it’s usually a team effort. This is not the domain of the lone wolf. When you consider the planning involved and number of highly specialized and skilled individuals needed to pull off a heist like the one at Pearson, you might think, “Why can’t we use that kind of planning to solve global poverty or that kind of coordination to prevent long lines at the DMV?” Alas, those issues aren’t quite as glitzy.

There is a reason that so many movies are made about colossal thefts—they take a certain brilliance to execute. And it’s usually a team effort. This is not the domain of the lone wolf. When you consider the planning involved and number of highly specialized and skilled individuals needed to pull off a heist like the one at Pearson, you might think, “Why can’t we use that kind of planning to solve global poverty or that kind of coordination to prevent long lines at the DMV?” Alas, those issues aren’t quite as glitzy.

A gold heist of this magnitude takes precision from the planning stage through distribution of the spoils, including knowing when the gold will be shipped, how much gold there will be, how it will be packaged, who will extricate it from the holding area and how, where it will be hidden, who will melt it down and how it will get to that person, how the melted gold will be sold and distributed, how the proceeds will be divided amongst the thieves, and most importantly, how they will avoid being caught. There are innumerable single points of failure that must be accounted for. Masterminding those details is part of the excitement and allure of the heist.

Gold is unique among high-value targets for thieves in that it can be melted down and cast into different shapes, rendering it distinct from its original form. Quickly melting and reshaping the stolen gold makes it easier to sell on the black market and is one of the reasons why gold continues to be so attractive to criminals. Additionally, of course, gold has never lost its monetary value or its cultural luster—market value may fluctuate but demand for this metal endures.

The black market for gold is so efficient that some believe gold jewelry purchased in Britain after 1984 probably contains bits of the gold from one of the greatest gold heists of all time: the Brink’s-Mat robbery at London’s Heathrow Airport. In November of 1983, six armed men, including a Brink’s-Mat security guard, stormed a warehouse at the airport, disarmed the electronic security systems, and poured gasoline on the guards, threatening to set them alight if they didn’t provide the combination to the safe. Expecting to find £3 million in gold, they found themselves in the presence of £26 million in gold bullion, diamonds, and cash (worth more than £87 million today). The thieves quickly sent for bigger trucks.

It took them two hours to haul out 6,800 gold bars (packaged into 76 crates) and £100,000 worth of cut and uncut diamonds. This unexpected volume of gold forced them to engage a prominent figure in the London underworld – “The Fox” – whose connections to one of London’s most notorious crime families provided the means to melt and distribute the gold. They then enlisted a jeweler to sell the melted down gold. It is estimated that fifteen people were involved in the Brink’s-Mat robbery, but only three were ever convicted and £20 million in bullion has never been recovered.

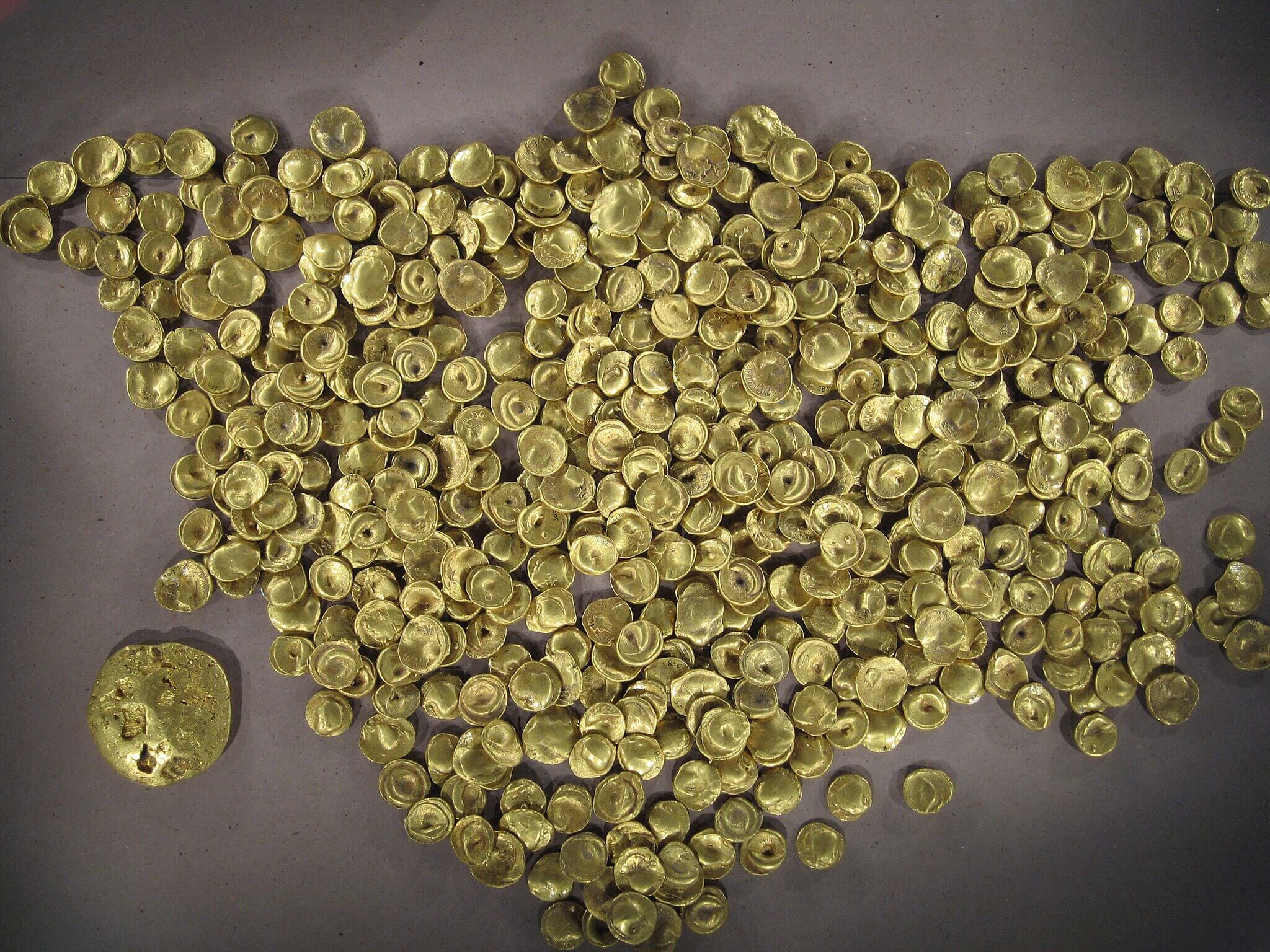

The Celtic-Roman Museum in Manching, Germany suffered the theft of 483 Celtic gold coins and a lump of unworked gold dating from 100 BC, in November of 2022. Thieves cut cables at a telecom hub about a mile from the site, knocking out internet service to the museum as well as most of the city. With the security system disabled and no guard at the museum overnight, they were able to break in, smash open the display cabinet containing the coins, and escape, all within nine minutes.

Celtic Coins found in Manching, Germany

The combined efforts of Interpol, Europol, and a 20-person investigations unit called, “Oppidium” (Latin for “Celtic settlement”) have led to the arrest of four German citizens, three of whom are believed to have carried out a dozen heists in Germany and Australia since 2014. However, only 18 of the gold coins have been recovered and authorities estimate that another 70 have been melted down. These coins are well-documented and, therefore, difficult to sell in their original form. In total, the material value of the coins, melted down, would be only €250,000 at current market prices, but as a collection of gold relics, their value would be around €1.65 million. Their cultural value, on the other hand, is priceless.

These bowl-shaped gold coins were discovered in a sack during an archaeological dig and are believed to comprise the war chest of a tribal chief. They were made from Bohemian river gold at a Celtic settlement and constitute the largest discovery of its kind in Germany during the 20th century. The find is significant both for the Manching community and for European archaeologists as it reveals a trade link between the Celtic settlement at Manching and those across Europe, and it helps to tell the story of how Germany was established. Markus Blume, Bavarian state minister for science and art, calls the heist, “an attack on our cultural memory.” Rupert Gebhard of the Bavarian State Archaeological Collection in Munich is hopeful that the coins will be recovered in their original state.

Gold heists are complex, thrilling, and cinematic. But they are also dangerous, violent, and often culturally and economically devastating. The mystical and monetary lure of gold has existed since its discovery and isn’t likely to disappear. The gold heist at Pearson, therefore, will surely not be the last!